Dictionaries

With lists, we stored things in order and accessed them by position.

That works… until your brain starts asking,

“What was at index 5 again?”

Dictionaries solve this by letting you use names instead of numbers, which feels a lot more human.

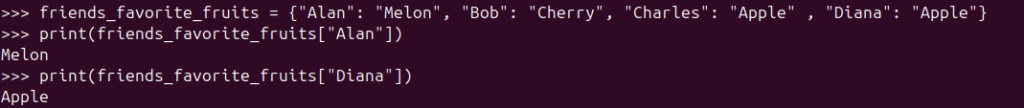

Consider your friend and their favorite fruit — we can translate this relationship into Python code:

friends_favorite_fruits = {

"Alan": "Melon",

"Bob": "Cherry",

"Charles": "Apple",

"Diana": "Apple"

}You can ask what your friend’s favorite fruit is by accessing the dictionary using the friend’s name:

friends_favorite_fruits["Alan"]Keys and values: finally, data with names instead of numbers.

As you can see, a dictionary is a collection of key–value pairs.

Each key is connected to a value. The key is used when we want to access its value.

A value can be any data type: a number, a string, a list, or even another dictionary.

A dictionary is defined using curly braces {}.

We can create an empty dictionary like this:

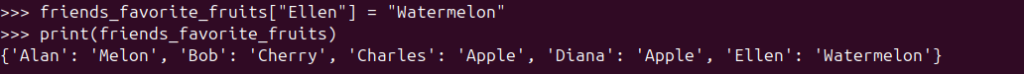

empty_dictionary = {}To add a new key–value pair to a dictionary, specify the key and assign a value to it:

friends_favorite_fruits["Ellen"] = "Watermelon"Adding a new key–value pair to the dictionary.

Dictionary keys are usually strings or numbers, but technically they can be any immutable data type. The key and value types don’t have to match other entries:

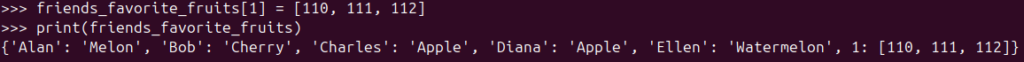

friends_favorite_fruits[1] = [110, 111, 112]

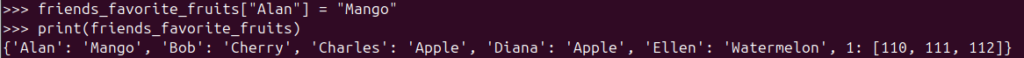

To modify the value of an existing key, just assign a new value to that key:

friends_favorite_fruits["Alan"] = "Mango"Same key, new opinion. Dictionaries update values, not memories.

You might notice that using an existing key updates its value instead of adding a new entry.

This means all keys in a dictionary must be unique.

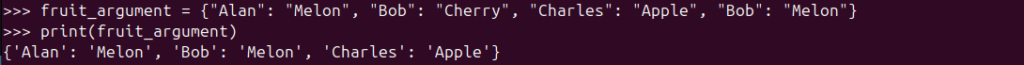

If you try to define the same key more than once, Python keeps the last value:

fruit_argument = {

"Alan": "Melon",

"Bob": "Cherry",

"Charles": "Apple",

"Bob": "Melon"

}Duplicate keys? Python listens to the last person who speaks.

Yes, Bob changed his mind. Python believed him.

Also notice two things:

- Python preserves insertion order for dictionary keys

- Multiple keys can share the same value

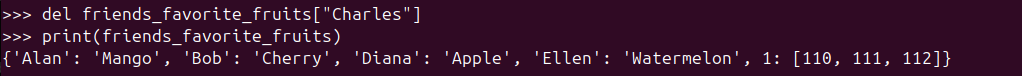

To delete a key–value pair, use the del statement (just like with lists):

del friends_favorite_fruits["Charles"]Removing a key–value pair with del. Clean and decisive.

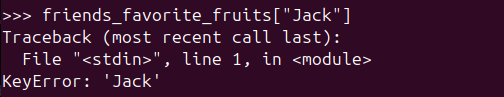

Be careful when accessing a key that doesn’t exist. Python will raise an error:

friends_favorite_fruits["Jack"]Accessing a key that doesn’t exist. Python is not amused.

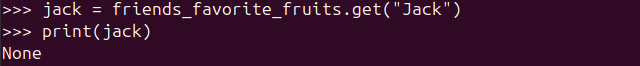

To avoid this, use the get() method:

friends_favorite_fruits.get("Jack")Using .get() to ask nicely instead of crashing the program.

If the key doesn’t exist, get() returns None.

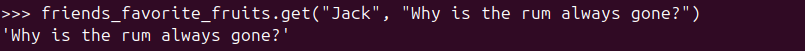

You can also provide a default value:

friends_favorite_fruits.get("Jack", "Why is the rum always gone?")Providing a default value when the key is missing.

Looping Through a Dictionary

When we want to walk through a dictionary, Python gives us several options.

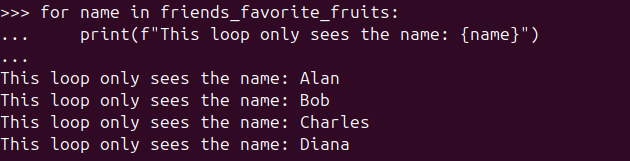

The simplest (and very common) way is looping over the keys:

for name in friends_favorite_fruits:

print(f"This loop only sees the name: {name}")Looping through a dictionary gives you keys by default.

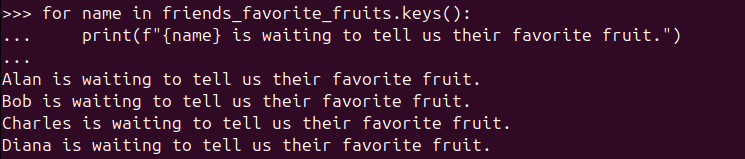

You can also be explicit and use keys():

for name in friends_favorite_fruits.keys():

print(f"{name} is waiting to tell us their favorite fruit.")Explicitly looping through keys with keys().

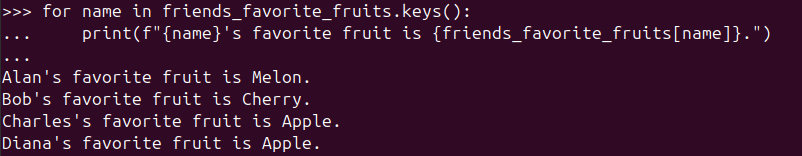

To print both the key and its value:

for name in friends_favorite_fruits.keys():

print(f"{name}'s favorite fruit is {friends_favorite_fruits[name]}.")Using keys to look up their corresponding values.

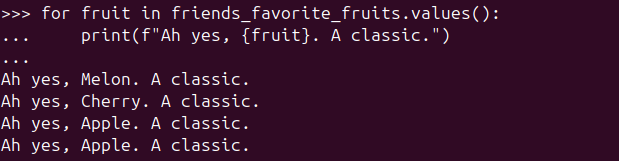

You can loop through values only:

for fruit in friends_favorite_fruits.values():

print(f"Ah yes, {fruit}. A classic.")Looping through values only. No keys involved.

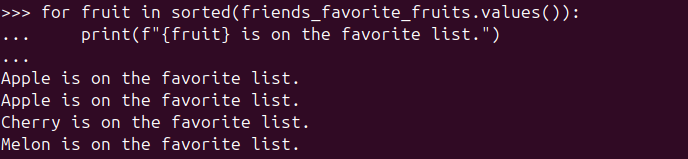

You can even sort them before looping:

for fruit in sorted(friends_favorite_fruits.values()):

print(f"{fruit} is on the favorite list.")Sorted values, because sometimes order does matter.

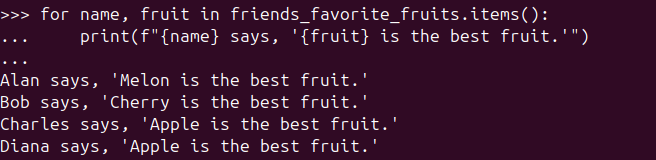

To access both keys and values at the same time, use items():

for name, fruit in friends_favorite_fruits.items():

print(f"{name} says, '{fruit} is the best fruit.'")Looping through both keys and values with items().

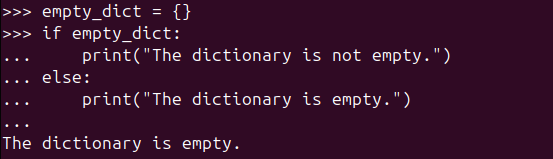

You can also check whether a dictionary is empty using an if statement

(this works for lists, too):

empty_dict = {}

if empty_dict:

print("The dictionary is not empty.")

else:

print("The dictionary is empty.")It failed the if-test or went to else-block.

The Next Step with Data Structures

We can combine data structures to represent more complex data.

For example, let’s store pizza information. Each pizza has:

- crust

- size

- toppings

- whether it’s spicy

Here, toppings is a list, and each pizza is stored as a dictionary inside a larger dictionary:

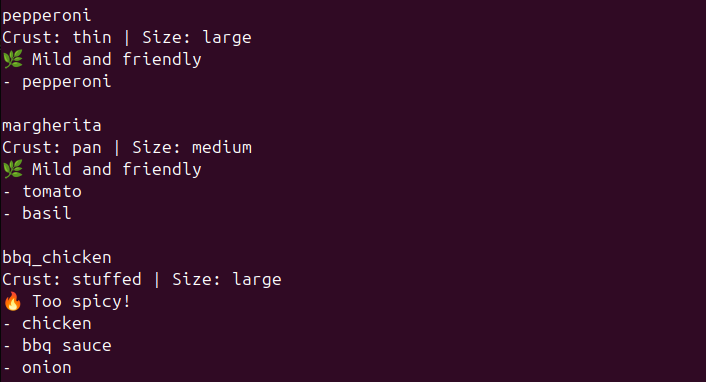

pizzas = {

"pepperoni": {

"crust": "thin",

"size": "large",

"toppings": ["pepperoni"],

"is_spicy": False

},

"margherita": {

"crust": "thin",

"size": "medium",

"toppings": ["tomato", "basil"],

"is_spicy": False

},

"bbq_chicken": {

"crust": "stuffed",

"size": "large",

"toppings": ["chicken", "bbq sauce", "onion"],

"is_spicy": True

}

}We can test the is_spicy value with an if statement and loop through toppings normally:

for pizza_name, pizza in pizzas.items():

print(f"\n{pizza_name}")

print(f"Crust: {pizza['crust']} | Size: {pizza['size']}")

print("🔥 Too spicy!" if pizza["is_spicy"] else "🌿 Mild and friendly")

for topping in pizza["toppings"]:

print(f"- {topping}")Dictionaries holding lists: welcome to nested data.

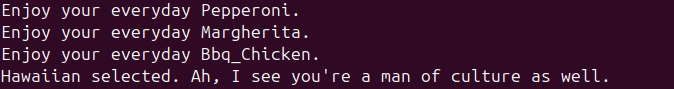

Let’s add one more pizza:

pizzas["hawaiian"] = {

"crust": "pan",

"size": "large",

"toppings": ["ham", "pineapple"]

}We can use the in keyword to check whether something exists in a collection:

for pizza_name, pizza in pizzas.items():

if "pineapple" in pizza["toppings"]:

print(f"{pizza_name.title()} selected. Ah, I see you're a man of culture as well.")

else:

print(f"Enjoy your everyday {pizza_name.title()}.")Using in to check if pineapple exists (important check).

This works because "pineapple" in toppings checks whether the string exists inside the toppings list.

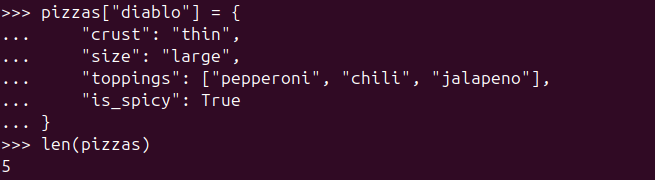

Let’s add one more pizza and confirm how many pizzas we have:

pizzas["diablo"] = {

"crust": "thin",

"size": "large",

"toppings": ["salami", "olive", "pepperoni", "chili", "jalapeno"],

"is_spicy": True

}

len(pizzas)We now have 5 pizzas.

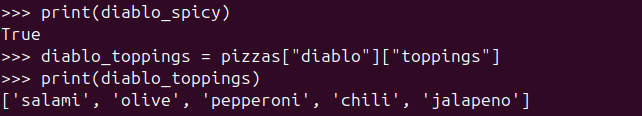

We can access nested values directly from pizzas:

diablo_spicy = pizzas["diablo"]["is_spicy"]

diablo_toppings = pizzas["diablo"]["toppings"]Accessing deeply nested values from the dictionary.

Quick Recap 🧠

- A dictionary stores data as key–value pairs, which makes it great for describing things with properties.

- You access values using square brackets:

pizza["toppings"], or safely with.get()to avoid surprises. - Dictionaries can hold anything: strings, numbers, lists, even other dictionaries.

- You can loop through a dictionary using:

keys()→ just the keysvalues()→ just the valuesitems()→ both, at the same time

- The

inkeyword helps you check whether a key (or value) exists. - Nesting dictionaries lets you model more realistic data — like pizzas with crusts, sizes, and toppings 🍕.

At this point, you can already describe complex data in a clean and readable way.

And yes — your code now understands pizza. That’s real progress.

🧠 Mini Challenge 1: Favorite Fruit Lookup

Challenge:

Given this dictionary:

friends_favorite_fruits = {

"Alan": "Melon",

"Bob": "Cherry",

"Charles": "Apple"

}Write code to:

- Print Alan’s favorite fruit

- Print a friendly message if the person doesn’t exist in the dictionary

Try it before scrolling 👀

💡 Spoiler: Solution

print(friends_favorite_fruits.get(“Alan”))

fruit = friends_favorite_fruits.get(“Jack”)

if fruit:

print(f”Jack likes {fruit}.”)

else:

print(“Jack is a mystery. No fruit data found.”)

🧠 Mini Challenge 2: Deep Access Practice

Challenge:

Access and store:

- Whether the diablo pizza is spicy

- How many toppings it has

💡 Spoiler: Solution

💡 Spoiler: Solution</summary>

is_spicy = pizzas["diablo"]["is_spicy"]

topping_count = len(pizzas["diablo"]["toppings"])

print(is_spicy)

print(topping_count)-

From Variables to Real-World Objects

When Code Starts to Look Like the Real World Object-Oriented Programming, or OOP, is…

-

Teaching Python to Do the Same Thing Twice

We know what a variable is. It is a label that points to a…

-

When Data Starts Having Names: Living With Dictionaries

Dictionaries With lists, we stored things in order and accessed them by position. That…

Leave a Reply