We know what a variable is. It is a label that points to a value. With variables, you can reuse that value again and again without needing to type it repeatedly. This is especially useful when a variable points to a calculated value. You calculate or process it once, and then reuse it throughout the rest of your program.

A function is similar, but instead of naming a value, it represents a block of code. This is incredibly helpful because it promotes code reuse and better code organization.

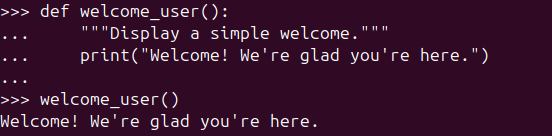

Let’s take a look at a simple function named welcome_user() that prints a greeting:

def welcome_user():

"""Display a simple welcome."""

print("Welcome! We're glad you're here.")

welcome_user()When Python sees the keyword def, it knows we are defining a function. After def comes the function name — in this case, welcome_user. After that, we specify the input of the function (parameters) inside parentheses.

This function does not need any input, so we leave the parentheses empty. However, the parentheses cannot be omitted, even if there are no arguments. This is different from some languages like Scala.

The function name and its parameters together form the function definition. We end the definition with a colon (:), just like with if statements or while loops. This colon tells Python that the indented lines that follow are the function body.

The second line is a special comment called a docstring, which describes what the function does. A docstring is placed immediately after the function definition and is used when Python generates documentation for your code. The triple quotes allow you to write multi-line descriptions if needed.

The line print("Welcome! We're glad you're here.") is the actual code inside the function body. This line is executed whenever the function is called. To call a function, we write its name followed by parentheses. Since welcome_user takes no arguments, we leave the parentheses empty.

When we call this function, the message Welcome! We're glad you're here. is printed.

A simple function that runs when we call it.

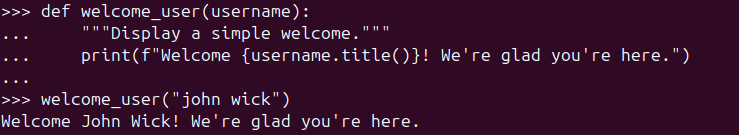

When we want to pass input to a function, we put it inside the parentheses. Suppose we want welcome_user to greet a user by name. We can modify the function like this:

def welcome_user(username):

"""Display a simple welcome."""

print(f"Welcome {username.title()}! We're glad you're here.")

welcome_user("john wick")

Adding a parameter lets the function work with outside data.

Here, username in the function definition is a parameter. A parameter is a piece of information the function needs to do its job."john wick" in the function call is an argument. An argument is the actual value passed into the function.

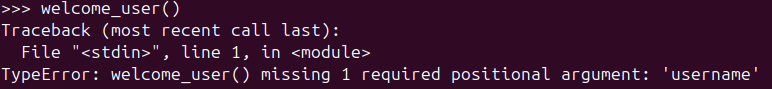

Now our function requires one parameter. If we forget to pass it, Python will raise an error:

Python complains when a required argument is missing.

A function definition can have multiple parameters, and Python gives us several ways to pass arguments to a function. Let’s explore them one by one.

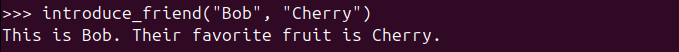

Positional Arguments

def introduce_friend(name, favorite_fruit):

"""Introduce a friend and their favorite fruit."""

print(f"This is {name}. Their favorite fruit is {favorite_fruit}.")This function accepts two parameters. The simplest way to pass arguments is by providing them in the same order as defined:

introduce_friend("Bob", "Cherry")

Positional arguments are matched by their position.

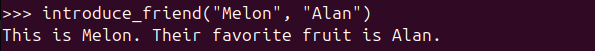

Python doesn’t care about the parameter names here — it only cares about their position. If we pass arguments in the wrong order, we may get unexpected results:

introduce_friend("Melon", "Alan")

Wrong order means wrong meaning.

If you see funny output, always double-check the argument order.

Keyword Arguments

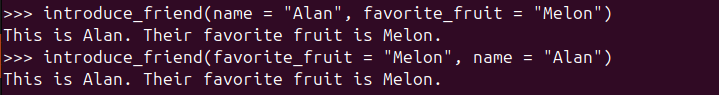

Another way to pass arguments is by explicitly matching values to parameter names. This makes your code clearer and avoids order-related mistakes. These two calls produce the same result:

introduce_friend(name="Alan", favorite_fruit="Melon")

introduce_friend(favorite_fruit="Melon", name="Alan")

Keyword arguments make the function call clearer and safer.

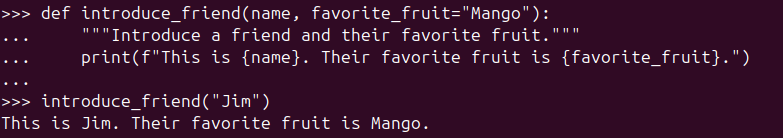

Default Values

When defining a function, we can give parameters default values. This allows the function to use those values when no argument is provided.

There is one rule: parameters with default values must come after parameters without default values.

For example, if most of our friends like mango, we can write:

def introduce_friend(name, favorite_fruit="Mango"):

"""Introduce a friend and their favorite fruit."""

print(f"This is {name}. Their favorite fruit is {favorite_fruit}.")Now we can call the function without specifying the fruit:

introduce_friend("Jim")

Default values are used when no argument is provided.

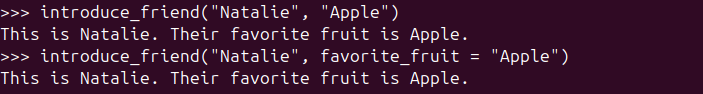

Of course, we can still override the default:

introduce_friend("Natalie", "Apple")

introduce_friend("Natalie", favorite_fruit="Apple")

Providing an argument overrides the default value.

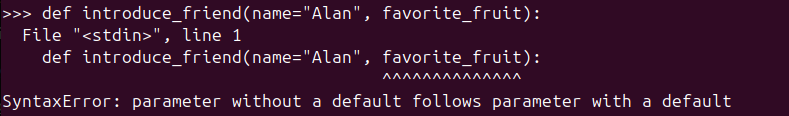

Python will raise an error if we place a default parameter before a non-default one:

def introduce_friend(name="Alan", favorite_fruit):

Defaults only work if required parameters come first.

Return Values

The idea of a function comes from mathematics. In math, a function takes an input and produces an output. For example:

F(x) = x * 2

If we pass 5, we get 10. In Python, functions can also return values.

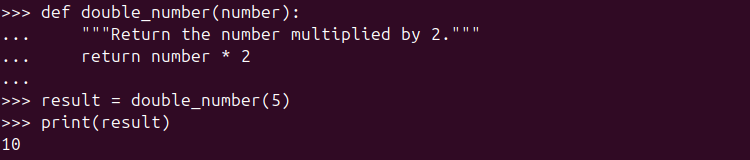

Here’s how we express that idea in Python:

def double_number(number):

"""Return the number multiplied by 2."""

return number * 2

result = double_number(5)

print(result)

Functions can return values instead of just printing them.

Passing and Returning Complex Data Structures

Functions are not limited to strings or numbers. They can receive and return complex data structures like lists and dictionaries.

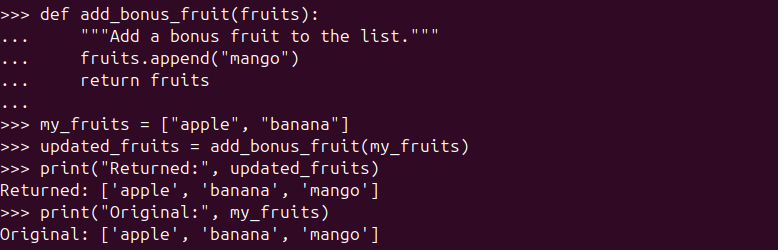

In this example, the function receives a list and returns a list:

def add_bonus_fruit(fruits):

"""Add a bonus fruit to the list."""

fruits.append("mango")

return fruits

A function can accept a list as its input.

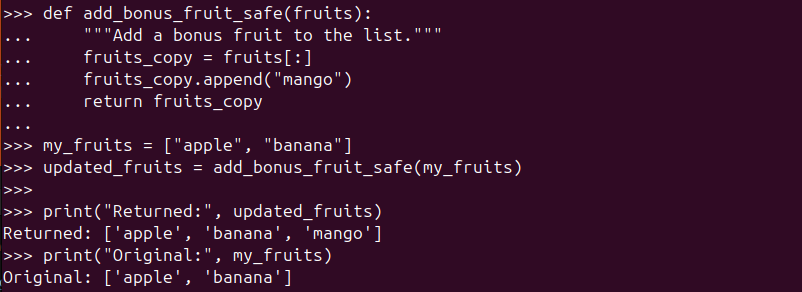

As you can see, lists are mutable. Changes made inside the function affect the original list. This may be intentional, but it can also introduce bugs and reduce reusability.

To avoid modifying the original list, we can use slicing to create a copy.

List Slicing

Slicing lets us work with parts of a list. The syntax is:

list[start:end]The start index is inclusive, and the end index is exclusive.

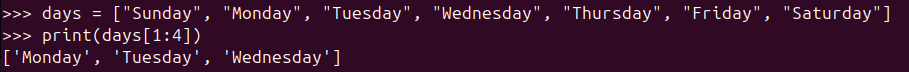

Examples with days of the week:

days = ["Sunday", "Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday", "Thursday", "Friday", "Saturday"]

print(days[1:4])

Basic slicing: selecting part of a list.

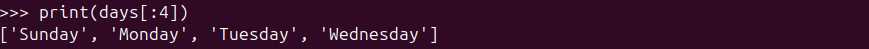

If we omit the start index, slicing begins at the start of the list:

print(days[:4])

Omitting the first index means “start from the beginning.”

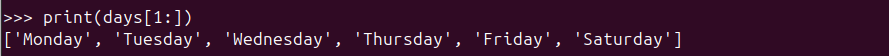

If we omit the end index, slicing goes to the end:

print(days[1:])

Omitting the second index means “go until the end.”

Negative indices count from the end:

print(days[-3:])

Negative indexes count from the end of the list.

You can mixed them together:

print(days[1:-3])

Slicing can mix positive and negative indexes.

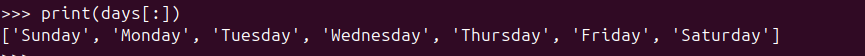

To copy an entire list, we use:

days[:]

Slicing the whole list creates a shallow copy.

This allows us to safely modify data inside functions without affecting the original list.

def add_bonus_fruit_safe(fruits):

"""Add a bonus fruit to the list."""

fruits_copy = fruits[:]

fruits_copy.append("mango")

return fruits_copy

Working on a copied list keeps the original data safe.

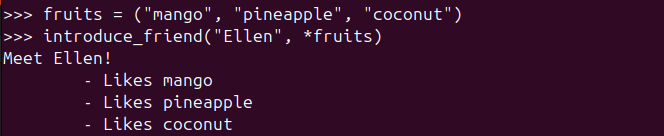

*args (Arbitrary Positional Arguments)

Sometimes we don’t know how many arguments a function will receive. Python solves this with *args.

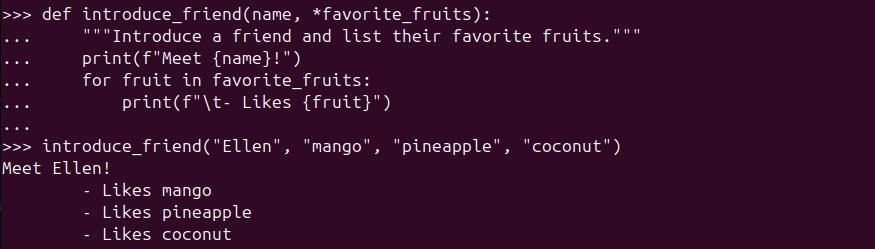

def introduce_friend(name, *favorite_fruits):

"""Introduce a friend and list their favorite fruits."""

print(f"Meet {name}!")

for fruit in favorite_fruits:

print(f"\t- Likes {fruit}")We can pass multiple fruits without knowing how many are there in advance:

*args lets a function accept any number of positional arguments

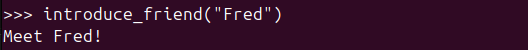

This function call is also valid:

introduce_friend("Fred")

When no extra arguments are passed, args is an empty tuple.

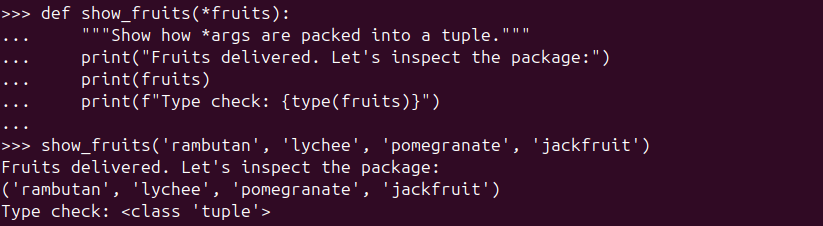

Behind the scenes, Python packs *args into a tuple.

def show_fruits(*fruits):

"""Show how *args are packed into a tuple."""

print("Fruits delivered. Let's inspect the package:")

print(fruits)

print(f"Type check: {type(fruits)}")

Python packs *args into a tuple behind the scenes.

A small but important note about *args

One thing to notice here: fruits is a tuple, not a list.

Tuples are immutable, which means they can’t be changed after they’re created.

That’s actually a good thing in this case. It acts like a safety feature — the function can read the values you pass in, but it can’t accidentally change them. This helps avoid surprising bugs and keeps your data predictable.

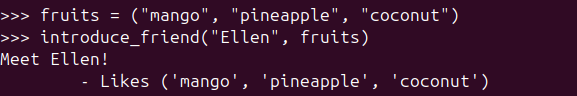

However, if we already have a tuple and pass it directly, the result may not be what we expect:

fruits = ("mango", "pineapple", "coconut")

introduce_friend("Ellen", fruits)

Not what we need!

Here, Python treats the entire tuple as a single argument, so the function sees one fruit — a tuple — instead of three separate fruits.

To fix this, we need to unpack the tuple using *:

fruits = ("mango", "pineapple", "coconut")

introduce_friend("Ellen", *fruits)

Now each item in the tuple is passed as its own argument, which is exactly what *args expects.

Rule of thumb:

- Use

*when you want to unpack a collection into separate positional arguments. - Use

*argsin a function when you want to receive any number of positional arguments.

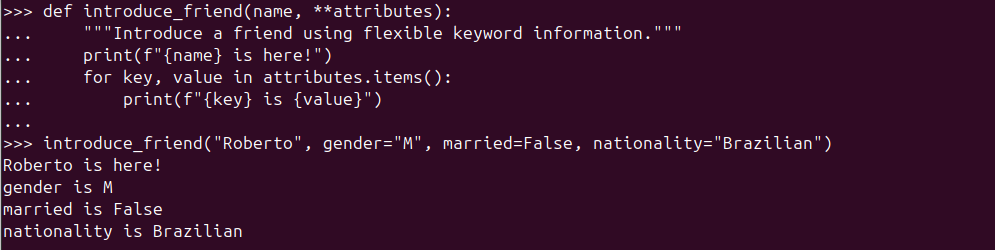

**kwargs (Arbitrary Keyword Arguments)

So far, all of our functions expected a fixed set of inputs.

We knew exactly what information would be passed in, and we defined parameters for each one.

But what if we don’t know ahead of time what extra information might be included?

That’s where Arbitrary Keyword Arguments, or **kwargs, come in.

Let’s say we want to introduce our friends again — but this time, we don’t want to limit ourselves to just a name.

Maybe we want to include their gender, nationality… or anything else that feels useful later.

Here’s how we can do that:

def introduce_friend(name, **attributes):

"""Introduce a friend using flexible keyword information."""

print(f"{name} is here!")

for key, value in attributes.items():

print(f"{key} is {value}")Now let’s call the function:

introduce_friend("Roberto", gender="M", married=False, nationality="Brazilian")

**kwargs captures extra keyword arguments.

What’s happening here?

namereceives"Roberto"as usual- Everything else (

gender,married,nationality) is collected intoattributes - Python automatically packs those extra keyword arguments into a dictionary

That’s why we can loop over attributes.items() — because it is a dictionary.

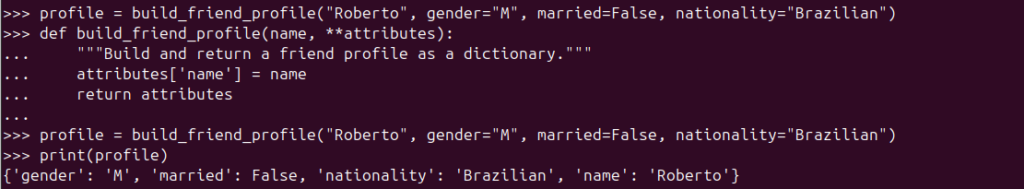

**kwargs is just a dictionary (behind the scenes)

To prove this, let’s build and return a friend profile:

def build_friend_profile(name, **attributes):

"""Build and return a friend profile as a dictionary."""

attributes['name'] = name

return attributes

profile = build_friend_profile("Roberto", gender="M", married=False, nationality="Brazilian")

Python stores **kwargs as a dictionary.

Here, we treat attributes exactly like a normal dictionary:

- we add a new key (

name) - we return it

- and we get a complete profile back

Nothing special — just a dictionary that Python created for us automatically.

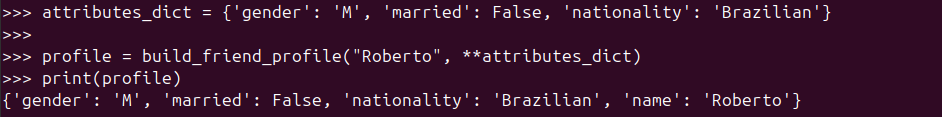

What if we already have a dictionary and want to pass it into the function?

Just like with *args, we need to unpack it first.

attributes_dict = {'gender': 'M', 'married': False, 'nationality': 'Brazilian'}

profile = build_friend_profile("Roberto", **attributes_dict)

A dictionary can be unpacked into keyword arguments.

Here’s the rule of thumb again:

**kwargscollects keyword arguments into a dictionary**unpacks a dictionary into keyword arguments

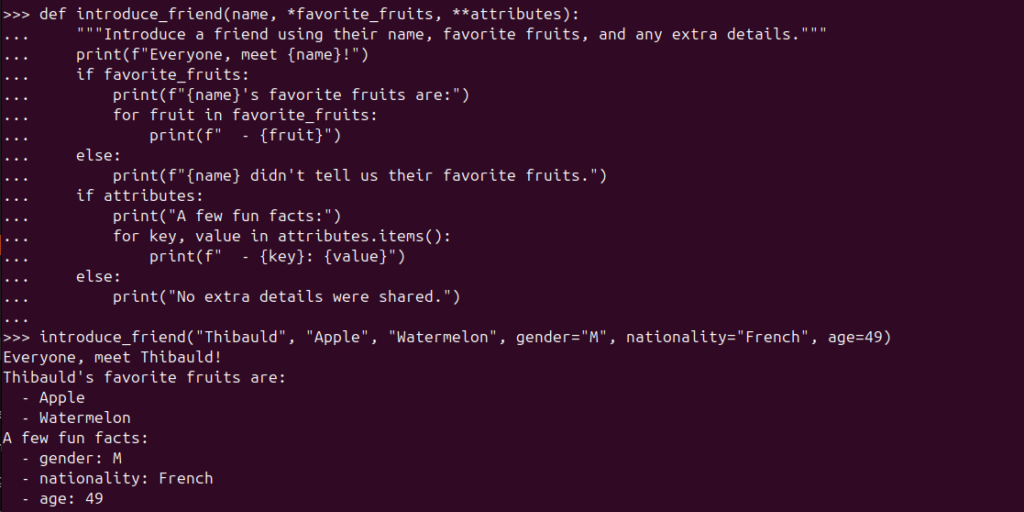

Mixing everything together: regular parameters, *args, and **kwargs

What if we want all three types of parameters in a single function?

Python actually has a very clear (and strict) rule for this.

The order must always be:

- Regular parameters

*args(arbitrary positional arguments)**kwargs(arbitrary keyword arguments)

If you break this order, Python will complain immediately.

Here’s a function that uses all three correctly:

def introduce_friend(name, *favorite_fruits, **attributes):

"""Introduce a friend using their name, favorite fruits, and any extra details."""

print(f"Everyone, meet {name}!")

if favorite_fruits:

print(f"{name}'s favorite fruits are:")

for fruit in favorite_fruits:

print(f" - {fruit}")

else:

print(f"{name} didn't tell us their favorite fruits.")

if attributes:

print("A few fun facts:")

for key, value in attributes.items():

print(f" - {key}: {value}")

else:

print("No extra details were shared.")

introduce_friend("Thibauld", "Apple", "Watermelon", gender="M", nationality="French", age=49)

Regular parameters, *args, and **kwargs working together.

What’s happening here?

namegets the required value- any extra positional values become

favorite_fruits(a tuple) - any named values become

attributes(a dictionary)

This pattern is extremely common in real-world Python code, especially in libraries and frameworks.

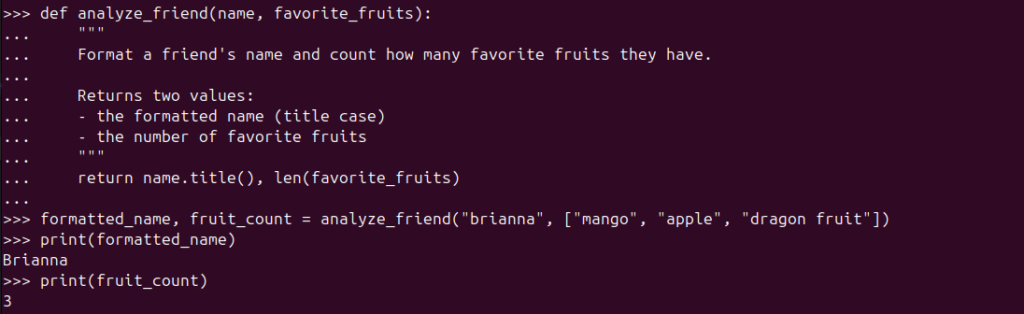

Returning multiple values from a function

Now that we’ve seen how flexible function inputs can be, let’s look at function outputs.

In Python, a function can return more than one value.

For example, let’s say we want a function that:

- formats a friend’s name

- tells us how many favorite fruits they have

We can write it like this:

def analyze_friend(name, favorite_fruits):

"""

Format a friend's name and count how many favorite fruits they have.

Returns two values:

- the formatted name (title case)

- the number of favorite fruits

"""

return name.title(), len(favorite_fruits)

formatted_name, fruit_count = analyze_friend("brianna", ["mango", "apple", "dragon fruit"])

print(formatted_name) # Brianna

print(fruit_count) # 3

What’s actually being returned here is a tuple.

We simply unpack it into two variables for convenience.

A small caution about returning multiple values

Even though returning multiple values is totally valid in Python, it can make code harder to:

- read (you must remember the order)

- test (what does index

0mean again?) - change later without breaking callers

If someone sees this without context:

result = analyze_friend(name, fruits)They won’t immediately know what result[0] or result[1] represents.

That’s a smell — not an error, but something to be careful about.

When returning multiple values works really well

Returning multiple values is a great choice when the values are:

- closely related

- obvious from the function name

- commonly used together

Here’s a classic example:

def get_min_max(numbers):

"""

Find the smallest and largest number in a list.

Returns two values:

- the minimum value

- the maximum value

"""

return min(numbers), max(numbers)

lowest, highest = get_min_max([3, 1, 5])This is instantly clear:

- no guessing

- no confusion

- very readable

A simple rule of thumb

- If the meaning of each returned value is obvious, returning multiple values is fine.

- If you need to explain what each value represents, a dictionary or object might be a better choice.

What is an object?

Don’t worry — we’ll get there soon.

-

Teaching Python to Do the Same Thing Twice

We know what a variable is. It is a label that points to a value.…

-

When Data Starts Having Names: Living With Dictionaries

Dictionaries With lists, we stored things in order and accessed them by position. That works……

-

Learning to Repeat Myself (the Smart Way)

When you want to repeat some tasks multiple times, or apply the same task to…

Leave a Reply