When Code Starts to Look Like the Real World

Object-Oriented Programming, or OOP, is a way of writing code that models how things work in the real world.

In real life, we think in objects:

- a hotel room

- a user account

- a car

Each of these things:

- has data (what it is)

- can perform actions (what it can do)

OOP brings this way of thinking directly into code.

Objects = Data + Behavior

An object is any entity that has attributes and behaviors. For example, a hotel room might have:

1. Properties (data)

Properties describe the object. They tell us the state of an object.

For a hotel room, this might be:

- room number

- capacity

- availability

2. Methods (behavior)

Methods describe what the object can do. They represent actions the object can perform.

For a hotel room, this might be:

- check in a guest

- check out a guest

- tell us whether it is available

OOP helps group related data and behavior together inside an object that owns them, rather than scattering them across the program.

Classes: Blueprints for Objects

Before we can create objects, we need a class.

A class is a blueprint or template that encapsulates properties and behavior into a single entity. It tells us:

- what properties an object will have

- what methods it can use

A class is not a physical thing. When you want to work with it, you create an object.

An object is a real entity whose properties and behaviors are defined by its class.

For example:

HotelRoomdescribes what any room isroom101androom102are real rooms created from that class

Keeping Code Organized as It Grows

1. Model real-world concepts naturally

Imagine explaining the program to someone else:

- A hotel has many rooms

- Each room has a number and a capacity

- Guests can check in and check out

When code is written this way, it becomes easier to:

- read

- explain

- remember

2. Keep related things together

Rather than having:

- one function changing availability

- another function checking capacity

- room numbers stored somewhere else

With OOP, everything related to a room lives inside the room. This makes the code feel more organized and intentional.

3. Let programs grow in a predictable way

Most programs start small… and then grow.

What begins as:

- one room

Can become:

- many rooms

- a hotel

- guests

OOP helps manage this growth by breaking complexity into clear, self-contained parts. Adding new features feels planned, not like dropping code in random places.

Your First Class (Even If It Does Nothing Yet)

To define a class, use the class keyword, followed by the class name and a colon.

Any indented code below it belongs to the class body.

class HotelRoom:

pass

We’ve defined a class called HotelRoom with no properties or methods.

The pass keyword does nothing—it’s just a placeholder.

Up to now, we’ve been writing Python in small snippets or an interactive prompt. That’s great for experiments, but once we start working with classes, it quickly becomes awkward.

From here on, we’ll write our code in Python files (.py). This is how Python is written in real projects and makes it easier to run, revisit, and grow our code over time.

Create a file (for example, hotel_room.py), then open a terminal and navigate to the file’s folder:

cd /path/to/your/py/fileRun the file with:

python hotel_room.pyor, if needed:

python3 hotel_room.pyNothing will be printed—and that’s expected. The file ran successfully, which means Python understands our class definition.

You can also run Python files using an IDE. Open the file and click Run, or right-click and choose Run Python File.

No output simply means there’s no code asking Python to print anything yet.

This may feel underwhelming, but this empty class is the foundation. From here, we’ll slowly add meaning, behavior, and rules—one step at a time.

From Blueprint to Actual Room

To create an object (also called instantiation), write the class name followed by parentheses. We usually assign the new object to a variable:

class HotelRoom:

pass

room_one = HotelRoom()

print(room_one)

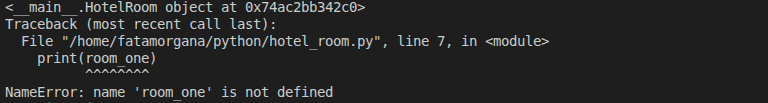

The output shows that room_one is an object, along with the memory address where Python stores it. Your memory address will be different.

We can create multiple objects from the same class. Each one is distinct:

room_one = HotelRoom()

room_two = HotelRoom()

print(room_one == room_two) # False

Even though both objects come from the same class, they are different objects.

We can also delete an object using del:

room_one = HotelRoom()

print(room_one)

del room_one

print(room_one) # NameError

Adding a Class Docstring

Just like functions, classes can have docstrings. The docstring should be the first string in the class body.

class HotelRoom:

"""

Represents a hotel room in a hotel.

This class will be expanded step by step.

"""

passNaming Classes the Python Way

While not mandatory, Python has naming conventions that improve readability.

- Use PascalCase (UpperCamelCase)

- Each word starts with a capital letter

- No underscores

Example:HotelRoom

- Capitalize acronyms

HTTPServerErroris preferred overHttpServerError

- Exception classes end with

Error- Example:

ValueError

- Example:

- Built-in classes are lowercase

list,dict,tuple

Class Properties: Shared State

Let’s add a shared piece of information to our class:

class HotelRoom:

"""

Represents a hotel room.

All rooms belong to the same hotel.

"""

hotel_name = "Hotel California"Create two rooms:

room_one = HotelRoom()

room_two = HotelRoom()Dot notation

You access data on objects using dot notation:

object.propertyto readobject.property = valueto change

print(room_one.hotel_name) # Hotel California

print(room_two.hotel_name) # Hotel California

print(room_one.hotel_name == room_two.hotel_name) # True

Because hotel_name belongs to the class, all objects see the same value.

Changing the class property affects every room:

HotelRoom.hotel_name = "Grand Budapest Hotel"

print(room_one.hotel_name) # Grand Budapest Hotel

print(room_two.hotel_name) # Grand Budapest Hotel

print(room_one.hotel_name == room_two.hotel_name) # True

Changing the class property updates the value for all objects.

Changing it on one object creates a separate value for that object only:

room_one.hotel_name = "Hotel Transylvania"

print(room_one.hotel_name) # Hotel Transylvania

print(room_two.hotel_name) # Grand Budapest Hotel

print(room_one.hotel_name == room_two.hotel_name) # False

Overriding a class property on one object affects only that object.

Python looks for a property on the object first. If it doesn’t find one, it falls back to the class.

You can remove the object-specific value with del to use the shared one again.

room_one.hotel_name = "Hotel Transylvania"

print(room_one.hotel_name) # Hotel Transylvania

print(room_two.hotel_name) # Grand Budapest Hotel

print(room_one.hotel_name == room_two.hotel_name) # False

del room_one.hotel_name

print(room_one.hotel_name) # Grand Budapest Hotel

print(room_two.hotel_name) # Grand Budapest Hotel

print(room_one.hotel_name == room_two.hotel_name) # True

After deleting the object’s own property, it falls back to the shared class value.

Instance Properties: What Makes Each Room Unique

Now, we want to differentiate one room from anoter. Different instances of HotelRoom should be unique, so guest wouldn’t check in to the same room. To make each room unique, we use __init__:

class HotelRoom:

"""

Represents a hotel room.

Each room has its own room number and capacity,

but all rooms belong to the same hotel.

"""

hotel_name = "Hotel California"

def __init__(self, room_no, capacity):

"""

Create a new HotelRoom object.

"""

self.room_no = room_no

self.capacity = capacityNow each room has its own identity.

Let’s create the room again:

room_one = HotelRoom("101", 1)

print(room_one.room_no) # 101

print(room_one.capacity) # 1

Instance properties belong to a single object and store its unique data.

When we instantiated room_one, Python automatically run __init__. The values we passed in were stored inside the object. This means room_no and capacity now belong to room_one instance, not the class. Each room can now have its own identity.

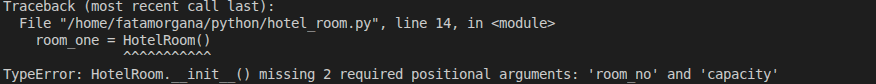

If you try to create a room without required arguments:

room_one = HotelRoom() # TypeError

Python raises an error—because the constructor expects values.

__init__ runs every time a new object is created. Because it prepares the object, it’s commonly called a constructor.

Who Is self, Anyway?

self refers to the current object. As we are instantiating a new HotelRoom, Python is saying “Create a new HotelRoom, and while setting it up, refer to this specific room as self“

Inside methods:

self.room_nomeans this room’s numberself.capacitymeans this room’s capacity

Without self, Python wouldn’t know where to store the data.

Imagine writing:

room_no = room_noThat wouldn’t make sense – it doesn’t say where the value should be stored.

By writing:

self.room_no = room_noWe’re clearly saying: Store this value inside this object.”

You can rename self, but don’t. It’s a convention everyone expects.

Methods: Teaching Objects How to Behave

Not only our class stores information, it can also do things. This is done through methods. Methods are functions that belong to a class and operate on its objects.

Let’s modify our HotelRoom:

class HotelRoom:

"""

Represents a hotel room with basic information.

It shows how a class stores data and defines behavior.

"""

hotel_name = "Hotel California"

def __init__(self, room_no, capacity):

"""

Creates a new HotelRoom object.

This method runs when a new room is created and

stores the room number and capacity on the object.

"""

self.room_no = room_no

self.capacity = capacity

def describe_room(self):

"""

Prints a short description of the room.

This method reads the room information from the object

and shows it on the screen.

"""

print(f"Room {self.room_no} with capacity {self.capacity}")The describe_room() method uses the room’s information and print it out. Note that all instance methods must have self as the first parameter. As in the constructor, self represents the current object. When you call the method on an object, Python automatically passes the object as self.

Every instance uses the same method, but the result depends on the object’s data.

Let’s call this method. Different objects have different output.:

room_one = HotelRoom("101", 1)

room_one.describe_room()

room_two = HotelRoom("102", 2)

room_two.describe_room()

From Information to Action

Methods can also change object data.

We add an availability property and methods to update it:

class HotelRoom:

"""

Represents a hotel room with basic details and availability status.

"""

hotel_name = "Hotel California"

def __init__(self, room_no, capacity):

"""

Create a new HotelRoom instance.

availability starts as True, meaning the room is available.

"""

self.room_no = room_no

self.capacity = capacity

self.availability = True

def describe_room(self):

"""

Print a short description of the room.

"""

print(f"Room number {self.room_no} with capacity {self.capacity}")

def check_in(self):

"""

Mark the room as occupied.

"""

self.availability = False

def check_out(self):

"""

Mark the room as available again.

"""

self.availability = True

def is_room_available(self):

"""

Return whether the room is currently available.

"""

return self.availabilityLet’s try it:

room_one = HotelRoom("101", 1)

room_one.check_in()Calling check_in makes the room update its own availability. We don’t even need to send an argument to the method.

Now, let’s check the availibity of this room:

room_one.is_room_available()🤔

Nothing is printed. Why?

Turn out that is_room_available() returns a value, not printing it. Calling a method that returns a value does nothing unless you print it:

print(room_one.is_room_available()) # FalseWhy Use Methods Instead of Changing Values Directly?

If I can just write:

room_one.availability = Falsewhy do I even need check_in()?

That’s a very good question. Let’s look at this:

room_one.availability = False

room_one.availability = False # again

room_one.availability = False # again...We want to change availability to False because guests are checking in.

Python allow this, but the object has no chance to stop you even if the room is already occupied.

Let’s improve check_in()

def check_in(self):

"""

Check in to the room only if it is available.

"""

if self.availability:

self.availability = False

print("Check-in successful.")

else:

print("Room is already occupied.")Now, the room can protect itself.

Let’s see it in action:

room_one = HotelRoom("101", 1)

room_one.check_in() # Check-in successful.

room_one.check_in() # Room is already occupied.

Methods can protect the object by preventing invalid actions.

Methods allow objects to:

- enforce rules

- prevent invalid actions

- protect their own state

This is why methods matter.

A Method That Affects All Rooms

So far, we’ve used methods to work with one specific room. But sometimes, we want to change something that applies to all rooms. For example: the hotel decides to change its name. Let’s do this with change_hotel_name() method:

class HotelRoom:

"""

Represents a hotel room with basic details and availability status.

"""

hotel_name = "Hotel California"

def __init__(self, room_no, capacity):

"""

Create a new HotelRoom instance.

availability starts as True, meaning the room is available.

"""

self.room_no = room_no

self.capacity = capacity

self.availability = True

def describe_room(self):

"""

Print a short description of the room.

"""

print(f"Room number {self.room_no} with capacity {self.capacity}")

def check_in(self):

"""

Check in to the room only if it is available.

"""

if self.availability:

self.availability = False

print("Check-in successful.")

else:

print("Room is already occupied.")

def check_out(self):

"""

Check out of the room if it is currently occupied.

"""

if not self.is_available:

self.is_available = True

print(f"Room {self.room_no} is now available.")

else:

print(f"Room {self.room_no} is already available.")

def is_room_available(self):

"""

Return whether the room is currently available.

"""

return self.availability

@classmethod

def change_hotel_name(cls, new_name):

"""

Change the hotel name for all rooms.

"""

cls.hotel_name = new_nameWhat is @classmethod?

It is used to decorate the function to define a class method. Here are the differences?

Instance method

- Works with one object

- Uses

self - Example: describing a room, checking in a room

Class method

- Works with the class itself

- Uses

clsinstead of self - Example: changing the hotel name for every room

Like self for object, cls is a standard in Python to refer to the class itself.

So, in this:

@classmethod

def change_hotel_name(cls, new_name):

cls.hotel_name = new_nameHere:

clsrefers to HotelRoomcls.hotel_namemeans the hotel name stored on the class

To call class methods, we call on class, not object:

HotelRoom.change_hotel_name("The Grand Ghibli Inn")Let’s try with our new class method:

room_one = HotelRoom("101", 1)

room_two = HotelRoom("102", 2)

print("==== before ====")

print(room_one.hotel_name) # Hotel California

print(room_two.hotel_name) # Hotel California

HotelRoom.change_hotel_name("The Grand Ghibli Inn")

print("==== after ====")

print(room_one.hotel_name) # The Grand Ghibli Inn

print(room_two.hotel_name) # The Grand Ghibli Inn

Wrapping It All Up

Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) is a way of writing code that feels closer to how we think about things in the real world. Instead of scattered variables and functions, we group related data and behavior together.

Class vs Object

- A class is a blueprint. It describes what something is and what it can do.

- An object (or instance) is a real thing created from that blueprint.

In our examples:

HotelRoom is the class

room_one and room_two are objects created from that class

Even if two objects are created from the same class, they are still different objects.

Properties and Methods

- Properties store information. Examples: room_no, capacity, is_available

- Methods define behavior. Examples: describe_room(), check_in(), check_out()

You can think of it like this:

- Properties describe what the object has

- Methods describe what the object can do

Class Properties vs Instance Properties

Class properties belong to the class itself. They are shared by all objects.

Example:

HotelRoom.hotel_nameInstance properties belong to a specific object. Each object can have its own values.

Example:

room_one.room_no

room_one.is_availableChanging a class property affects every object.

changing an instance property affects only that one object.

Accessing Properties and Methods

We use dot notation to work with objects:

room_one.capacity

room_one.describe_room()

room_one.check_in()Why Methods Matter

Even though we can change properties directly, methods give us control. They allow us to:

- keep the object in a valid state

- prevent mistakes (like checking in twice)

- make the code easier to understand and safer to use

Instead of saying how something should change, we just tell the object what we want to do.

Leave a Reply