When you want to repeat some tasks multiple times, or apply the same task to a group of data, it’s tempting to just write the same statement again and again.

For example, suppose we have a list that contains the days of the week:

days = ['Sunday', 'Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday']If you want to print out each day, the most straightforward (and painful) way would be:

print(days[0])

print(days[1])

print(days[2])

# ... until days[6]

# remember: the first index is 0, the last index is length - 1Now imagine the list has 1 million elements.

You’d have to copy-paste this a million times.

Then imagine a change request like: “Add Hello in front of every line.”

Congratulations — you now have a million edits to make.

That’s obviously not practical. Luckily, Python (and most programming languages) gives us better tools.

Before we get there, let’s take a short detour and talk about user input.

Getting Input from Users

Most non-trivial programs follow the same basic idea:

Input → Process → Output

Without input, programs don’t really do much.

One of the simplest ways to accept user input in Python is with the built-in input() function. It pauses the program, waits for the user to type something, and then returns that value.

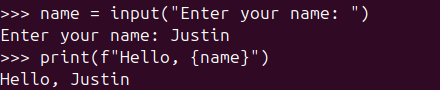

Example:

name = input("Enter your name: ")

print(f"Hello, {name}")Python politely pauses and waits for the human to say something.

Input Is Always a String

This is important.

No matter what the user types, input() always returns a string.

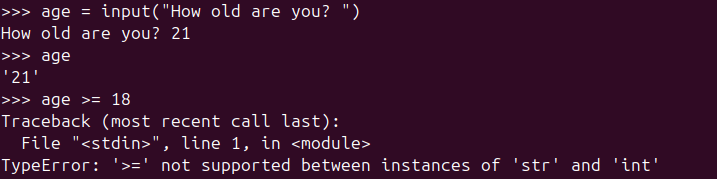

For example:

age = input("How old are you? ")

age >= 18User input is always a string — numbers included. Python is not fooled.

Even if the user types 21, Python still sees it as '21' (a string).

Comparing a string to an integer causes an error.

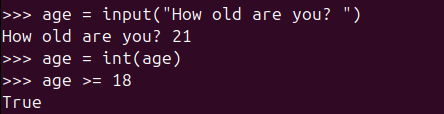

To fix this, we convert the input using int():

age = input("How old are you? ")

age = int(age)

age >= 18Converting user input to int so Python can finally do math.

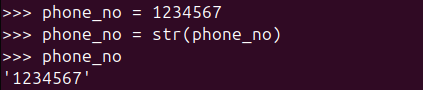

You can convert values the other way around too. For example, converting a number into a string using str():

phone_no = 1234567

phone_no = str(phone_no)

phone_noTurning a number into text so it can behave nicely with strings.

With that out of the way, we’re ready to talk about repetition.

The while Loop

Use a while loop when you want to repeat some code as long as a condition remains true.

General structure:

do before

while condition:

do statement 1

do statement 2

do afterHere’s a simple example that counts from 1 to 5:

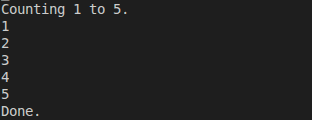

print("Counting 1 to 5.")

number = 1

while number <= 5:

print(number)

number += 1

print("Done.")A simple while loop counting from 1 to 5 — one step at a time.

A More Practical Example

We can also use a while loop when we don’t know in advance how many times the loop should run — for example, waiting for user input:

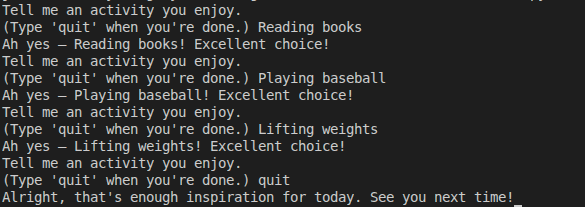

quit_condition = 'quit'

prompt = "Tell me an activity you enjoy."

prompt += f"\n(Type '{quit_condition}' when you're done.) "

activity = ""

while activity != quit_condition:

activity = input(prompt)

if activity != quit_condition:

print(f"Ah yes — {activity}! Excellent choice!")

print("Alright, that's enough inspiration for today. See you next time!")This loop keeps running until the user explicitly types quit.

The for Loop

When you want to run a block of code a known number of times, Python offers a cleaner option: the for loop.

Basic structure:

do before

for item in collection:

do statement 1

do statement 2

do afterPython executes the loop once for each item in the collection.

Introducing range()

The range() function generates a sequence of numbers.

Syntax:

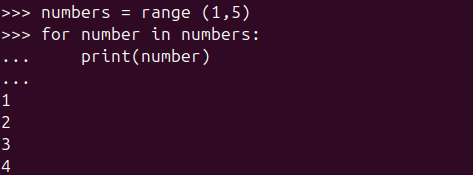

range(start_inclusive, end_exclusive)Example:

numbers = range(1, 5)

for number in numbers:

print(number)This prints 1, 2, 3, 4.

The ending value (5) is not included.

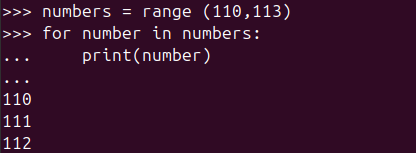

You can start anywhere:

numbers = range(110, 113)

for number in numbers:

print(number)range() can start from any number you like.

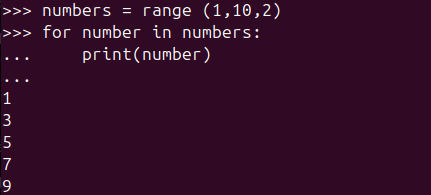

You can also control the step size:

numbers = range(1, 10, 2)

for number in numbers:

print(number)This prints odd numbers only.

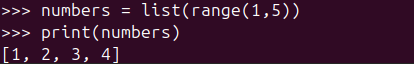

You can even convert a range into a list:

numbers = list(range(1, 5))

print(numbers)Turning a range() into a real list using list().

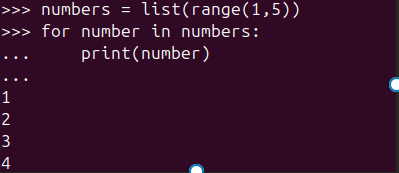

And loop over it the same way:

for number in numbers:

print(number)Using a for loop to walk through numbers generated by range().

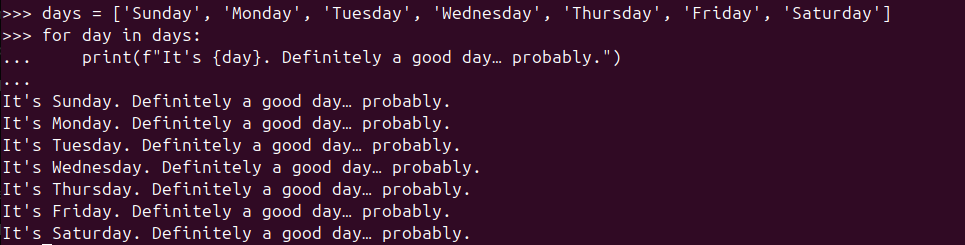

Looping Over Lists and Tuples

Back to our list of days:

days = ['Sunday', 'Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday']

for day in days:

print(f"It's {day}. Definitely a good day… probably.")Looping through a list — no indexes, no headaches.

This works for tuples as well:

days = ('Sunday', 'Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday')

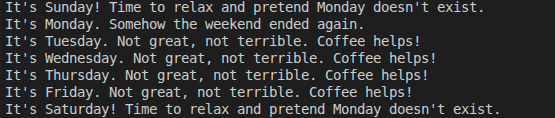

for day in days:

if day == 'Monday':

print(f"It's {day}. Somehow the weekend ended again.")

elif day == 'Sunday' or day == 'Saturday':

print(f"It's {day}! Time to relax and pretend Monday doesn't exist.")

else:

print(f"It's {day}. Not great, not terrible. Coffee helps!")Mixing for loops and if statements to make decisions per item.

continue and break

You can control loop execution using two keywords:

continue→ skip the rest of the current iterationbreak→ exit the loop immediately

Example:

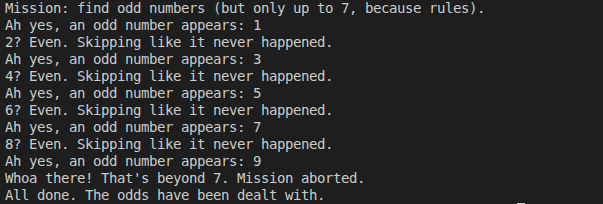

numbers = range(1, 11)

print("Mission: find odd numbers (but only up to 7, because rules).")

for number in numbers:

if number % 2 == 0:

print(f"{number}? Even. Skipping like it never happened.")

continue

print(f"Ah yes, an odd number appears: {number}")

if number > 7:

print("Whoa there! That's beyond 7. Mission aborted.")

break

print("All done. The odds have been dealt with.")continue skips ahead, break exits the loop — sometimes you just need boundaries.

Both continue and break also work in while loops.

while vs for

Although while and for loops can sometimes be used interchangeably, they serve different purposes.

forloops are best when you know how many times something should run

(for example, iterating over a list or a range).whileloops are best when you don’t know how many iterations you’ll need

(for example, waiting for user input, reading until EOF, or waiting for a stop signal).

A good rule of thumb:

If you can say “for each item…”, use a

forloop.

If you can say “while this is true…”, use awhileloop.

Common Mistake: Infinite Loops

Consider this working loop:

number = 1

while number <= 5:

print(number)

number += 1Now remove one line:

number = 1

while number <= 5:

print(number)This loop never ends.

Why?

Because number starts at 1 and never changes.

The condition number <= 5 is always True.

The program will happily print 1 forever.

When writing a while loop, always double-check:

- Is the condition able to become

False? - Is something inside the loop changing the state?

Indentation: Python’s Secret Sauce

In Python, indentation isn’t just about style — it’s part of the syntax.

Unlike languages such as Java or C#, which use {} to define code blocks, Python uses leading whitespace.

Rules to remember:

- All statements in the same block must be indented equally

- A colon (

:) means “the next line starts a new block” - Nested blocks require deeper indentation

- The standard is 4 spaces per level

Tabs technically work, but mixing tabs and spaces is a great way to summon confusing bugs. Stick to spaces.

Indentation tells Python what belongs where — get it wrong, and the program may behave incorrectly or refuse to run at all.

Quick Recap

- Repeating the same code by hand doesn’t scale — loops exist to save your sanity.

input()lets your program talk to humans (and politely wait for replies).- User input is always a string, even when it looks like a number.

- Use

whileloops when you don’t know how many times something will run. - Use

forloops when you do know, or when looping over a collection. range()helps generate numbers without writing them all yourself.continueskips to the next loop round;breakexits the loop completely.- Forgetting an exit condition in a

whileloop can lead to an infinite loop. - In Python, indentation isn’t optional — it defines how your code actually works.

🧩 Mini Challenge: Loop Like a Human

You are given a list of daily activities.

activities = ['coding', 'eating', 'sleeping', 'coding', 'doomscrolling', 'coding', 'quit', 'coding']

Your task:

- Loop through the list one item at a time

- When the activity is

'coding', print something encouraging - When the activity is

'doomscrolling', print a gentle warning - When the activity is

'quit', stop the loop immediately - Ignore everything else quietly (no output)

💡 Hint:

You’ll probably need for, if / elif, and either continue or break.

🕵️ Spoiler: One Possible Solution

Click to reveal the solution 👀

activities = ['coding', 'eating', 'sleeping', 'coding', 'doomscrolling', 'coding', 'quit', 'coding']

for activity in activities:

if activity == 'coding':

print("Coding detected. Good choice.")

elif activity == 'doomscrolling':

print("Warning: doomscrolling in progress. Consider closing the app.")

elif activity == 'quit':

print("Quit signal received. Exiting loop.")

break

else:

continue-

From Variables to Real-World Objects

When Code Starts to Look Like the Real World Object-Oriented Programming, or OOP, is…

-

Teaching Python to Do the Same Thing Twice

We know what a variable is. It is a label that points to a…

-

When Data Starts Having Names: Living With Dictionaries

Dictionaries With lists, we stored things in order and accessed them by position. That…

Leave a Reply