Let’s talk about data types and variables.

In Python, the concept of primitive and reference types is a bit blurry, because everything in Python is an object. A variable is treated more like a label pointing to a value, rather than a container that holds the value itself.

In Python, those “primitive-like” types are actually immutable types. This means they cannot be changed after they are created. Let’s look at an example:

y = x

print(f"y before: {y}")

x = x + 1

print(f"y after: {y}")

will produce:

Changes made to x after assigning it to y do not affect y.

This happens because x = x + 1 creates a new object, and x is updated to point to that new object, while y still points to the old one.

In this example, we use an f-string, which converts the value inside the curly braces {...} into a string automatically. This is useful because strings cannot be directly concatenated with integers. You could also use the str(...) function instead, but f-strings usually make the code cleaner and easier to read.

Immutable Types in Python

Here are the common immutable types in Python:

Numeric Types

int, float, complex

x = 10

x = x + 1 # creates a new objectBoolean Type

bool

flag = True # flag cannot be modified in placeText Type

str

s = "hello"

# s[0] = "H" gives TypeErrorTuple Type

tuple

t = (1, 2, 3)

# t[0] = 112 gives TypeErrorNote that even though a tuple itself is immutable, it can still contain mutable objects:

t = ([1, 2], [3, 4])

t[0].append(5) # validFrozen Set Type

frozenset

fs = frozenset([1, 2, 3])

# fs.add(4) gives AttributeErrorBytes Type

bytes

b = b"abc"

# b[0] = 100 gives TypeErrorNone Type

None

x = None # cannot be changedRange Type

range

r = range(10)

# r[0] = 5 gives TypeErrorMutable types include list, dict, set, bytearray, and most custom class instances. When you assign one variable to another, both variables point to the same object in memory. Let’s see an example:

x = [1,2,3]

y = x

print(f"y before:{y}")

x.append(9)

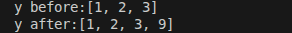

print(f"y after:{y}")will produce:

Initializing Variables

Next, let’s look at initializing variables.

In Python, we don’t need a special syntax to declare variables like in some other languages. For example, we don’t need to declare the type like this:

String me = "Python"

int i = 1We also don’t need declaration keywords like:

let name = "Bob"

def index = 11Instead, we can declare a variable directly using assignment:

message = "Hello, Python"

my_num = 1.12Python automatically infers the type of the variable, so message is a string and my_num is a number.

Once a variable is declared, its type can change at runtime. Python does not raise an error when you assign a value of a different type to the same variable. For example:

example = "I am string"

print(example)

example = 23

print(example)This code will produce the following output:

Variable Naming Rules

Like other programming languages, Python has rules for naming variables.

Variable names can contain letters (uppercase and lowercase), numbers, and underscores. They can start with a letter or an underscore, but not with a number. Variables also cannot contain spaces, but underscores can be used to separate words.

So this is valid:

message_1 = "Hello"But these are not:

1_message = "Hello"

message 1 = "Hello"Python uses the snake_case naming convention, where all characters are lowercase and words are separated by underscores. By convention, variables written in ALL CAPS are treated as constants.

Variable names must not be Python keywords or built-in function names. For example, writing:

print = "Hello"will override the built-in print() function and likely break your program.

🔴 Note: This will not cause a compile error, but it will shadow the built-in function and lead to confusing runtime behavior.

We’ll talk more about these data types in the upcoming posts.

Leave a Reply